A Happy Little Island Read online

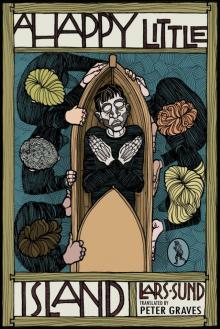

A Happy Little Island

Lars Sund

Translated by Peter Graves

In memory of Broge Wilén (1939-2006) and for Gudrun, of course, as always

“Death is the sanction of everything the storyteller can tell.” – Walter Benjamin

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

I The First Human Being

II The Sad Story of Celia and her Great Misfortune

III Deine Elisaveta

IV How Janne the Elder Was Miraculously Saved from the Sea and What Happened Afterwards

V The Cries of the Gulls

VI The Story of Kangarn, Who Began Life in a Ditch

VII The Search

VIII Beda Gustavsson Listens to Herself

IX We Visit Fagerö for the Last Time

Copyright

A Happy Little Island

In the beginning the computer screen was without form, and void; and the fingers of the scribe rested upon the keyboard.

The scribe chewed his lower lip, his glance flitting like a fly between the stuffed bookcases of his study, the rocking chair over by the window, the framed colour prints of birds on the walls. He went out to the kitchen and drank some water. Then he sat down at his computer again.

To create a fictional world from nothing, using only the tools that language places at our disposal, is truly a great and demanding undertaking!

The scribe hesitated and pondered for a long time before finally writing the first word: “Heaven”. After thinking again for a long while he wrote the following word, which was “Seas”.

And with that the heavens and the seas were created, but they were still not divided. The scribe solved that by laying out a horizon in the far distance, and he let it lie there unbroken, for the open horizon of the sea was the most beautiful view he knew.

Now the scribe became more and more energetic.

In the firmament of the heavens he set a sun to light his new world and he scattered some cumulus clouds, the latter mainly for decoration. Furthermore he made a light breeze blow from the south-south-west and he made it Force 2 on the wind scale created in 1805 by Commander Francis Beaufort while he and his vessel lay in Plymouth Sound awaiting orders to sail. The rays of the sun danced on the small waves that were driven along by the breeze.

The scribe needed a piece of dry land to anchor his story and so he wrote in a skerry in the sea. It was no more than a long narrow granite ridge, in shape and form rather like a capsized ship about to sink. On its north-west side flat slabs, rounded and smoothed by the inland ice, rose gradually from the waters, but on the south side the cliffs fell steeply down into the sea. The scribe created plants and animals on the skerry. Down at the waterline he stuck a fringe of saltwater lichens and blue-green algae on the rocks. Higher up he planted salt-marsh grass, sea campion and scentless mayweed, and then stonecrops and rock campion. On the rocky hillocks he laid low scrubby carpets of juniper, sea buckthorn, crowberry and heather; hairgrass, sheep’s fescue, sea speedwell and common toadflax were also permitted to grow there. In the crevices and hollows in the rocks, where cushions of sphagnum moss retain moisture, cotton grass, sundews and marsh lousewort flourished. Next the scribe brought forth herring gulls, common gulls and razorbills on the skerry, and also a colony of Arctic terns because he liked their elegant flight and their shrill, easily recognisable call – krii-ay, krii-ay, krii-ayay. He pencilled in the veins on the eggs ready to hatch in their downy nests hidden away among heather and crowberry. Common sandpipers, redshanks and ruddy turnstones completed his birdlife.

On the highest point of the skerry the scribe placed a stunted pine, scraggy, gnarled and crooked. The reason he chose that sort of gnarled undernourished variety of Pinus sylvestris is because it has often served as a symbol for the exposed life of the islanders, for their struggle to keep their distinctive identity and their right to their language. The stunted pine fits in very well in a story like this.

It occurred to the scribe to give the new land a name while he was at it. He called it Skogsskär, that is Forest Skerry. That, he thought, was the sort of name the islanders themselves would probably choose for a rocky little island on which there was nothing but a solitary windswept pine.

The scribe looked at his work and thought: “Right, that will have to do.”

And he set about creating the first human being.

Now, it might have been a relatively simple matter to create the heavens and the seas and a little skerry of an island with all the appropriate plants and birds, including a stunted pine on its top, but the scribe soon discovered that creating a human being was much more troublesome. When, after much toil and trouble, he finally completed his Adam, he was a sorry sight to behold.

Adam lay there on his belly in the shallows below the steep southern point of Skogsskär, the sea rocking him lazily and softly. The swell washed him gently against the cliffs, his forehead touching the rocks, then the swell sucked him back a little way before pushing him towards the shore again. The first human being submitted patiently to the sea’s game. He had one arm stretched out as though trying to grasp firm ground.

Patches of light split by the prisms of the waves moved gently along the seabed around his body. A tuft of green algae swayed a few inches in front of his wide-open eyes. The gulls, posted on stones and rock ledges, stood guard over him like soldiers in white dress uniforms with grey cloaks.

I

The First Human Being

To:policedepartment@countycouncil

From:[email protected]

Subject:unidentified body

At 12.51 today emergency services alerted the police that the body of an unknown male was in a boathouse at Tunnhamn on Fagerö. The inspector and Senior Constable Skogster proceeded there immediately and confirmed the accuracy of the report.

The body is that of a young man aged 25-30, height 176 cm, weight c. 70 kg, slender build, narrow face, sandy-coloured hair, blue eyes. No further particular distinguishing features. A small scar on the left side of the neck was noted but not considered relevant to the man’s death.

The deceased was wearing a white T-shirt and white underpants but no trousers. The deceased was not carrying any documents that enabled identification. According to preliminary reports the body was discovered on the small island called Skogsskär c. 10 nautical miles south-east of Fagerö. Those who found the body have not yet made themselves known but it is expected they will be traced and questioned in the course of the evening.

Kangarn’s boys were the ones who found him.

Look, there’s their boat coming across the firth at top speed. Heading straight down towards Skogsskär, which points to the crew being familiar with these difficult waters. You have to keep the stunted pine on the skerry lined up with the cairn on the island of Kårdiskan in order to avoid the reefs which some malevolent power has placed in the middle of the firth. Their boat, a Big Buster with a forty horsepower outboard, came into Kangarn’s hands a couple of years ago as part of a business deal – details are hazy. The boys have the use of the vessel most of the time since Kangarn is a very busy man who rarely has time to go out in a boat.

You can hear the powerful throb of the Evinrude motor echoing over the firth. The propeller cuts a long frothy wound of white foam in the sea. Every now and again the boat’s aluminium hull hits the groundswell with a dull thud and water splashes up around the blunt stem.

St Erik is half-reclining at the steering pulpit, one hand on the wheel, one foot resting on the rail, a lighted cigarette in his mouth. The wind snatches the smoke from his lips when he breathes out and it ruffles his dirty blond hair, which is the colour of the reed thatch on an o

ld boathouse. In the bows his twin brother St Olof is doubling up as lookout and marksman. He has binoculars hanging round his neck and a Sauer & Sohn drilling gun on his knee: the rifle barrel is loaded for seals, the two shotgun barrels for scoter and eider. The fact that the grey seal is a protected species and the spring hunting season for seabirds is over is of no great concern to St Olof. If the opportunity presents itself he will shoot, whatever the hunting laws may stipulate.

So there, dear reader, you have them – Kangarn’s boys.

On the Gunnarsholmar islands and in neighbouring parts of the archipelago they are called St Erik and St Olof. There is more than a hint of ill-concealed irony in the names, for sanctity and Christian virtue are not exactly traits that characterise Kangarn’s boys. When their names come up in conversation among respectable people, tongues are sharp with condemnation. The general feeling is that St Erik and St Olof will sooner or later end up in a penal institution atoning for their sins.

A couple of empty beer bottles are rolling around the bottom of the boat. There is a box in which three gleaming silver salmon with bloody gills are lying on top of a dozen or so flounders from which the seawater is still dripping. It’s a fine catch, no doubt about that, but it does beg a few questions. Neither Kangarn nor his sons own the fishing rights to waters out by Skogsskär – nor anywhere else as far as people are aware.

St Erik throttles back, turns to starboard and lets the Buster glide in close beneath the steep southern shore of Skogsskär, where the water is deep and there are no rocks. The cliffs of the skerry roll past like the backdrop of a revolving stage. The herring gulls utter harsh excited screams as they fly up in alarm. Out of habit St Erik’s eyes sweep along the water’s edge. You can never be sure what the sea decides to deliver up: timber washed overboard from the deck-load of some vessel, or boxes, cans, buoys or nets that have come adrift. The summer before, St Erik and St Olof salvaged a drum of petrol that was still half-full.

All of a sudden St Erik heaves himself up from the steering pulpit and shades his eyes with his hand.

“Hey, Olli! Looks like there’s a bloody seal over there by the skerry. Good one, too,” he calls to his brother in a low voice, just loud enough to be heard above the throb of the outboard.

St Olof, who is just about to fire off a shot at the circling gulls, lowers his gun.

“Where do you mean?”

“Over there by the cliff.”

St Erik points; St Olof raises his binoculars and searches.

“That’s not a seal,” St Olof says.

“What the fuck is it, then?”

St Erik puts the outboard motor into neutral and lets the boat drift close into shore. He judges the distance skilfully and at just the right moment gives the propeller a couple of turns in reverse and brings the boat to a halt with its prow just a couple of metres from whatever it is in the water. He puts the outboard in neutral again, clambers over the thwarts to his brother and leans over the rail.

St Olof is right. It isn’t a seal.

It takes a few moments for their brains to process what their eyes are seeing.

The keel of the boat thuds against a rock at the water’s edge.

“For fuck’s sake! It’s a body!” St Olof rasps and it sounds as if his mouth is lined with sandpaper.

“Fucking hell!”

“Jesus Christ!”

They fall silent. Their eyes meet. Each of them notices the cold light of fear in the other’s eyes. They look away simultaneously.

A moment later St Olof says to his brother: “Bloody hell, Erkki …”

Then stops short.

His mouth still sounds as if it’s lined with sandpaper but now of a slightly finer grade. St Olof is staring into the distance, right out to the open horizon. He can’t find a fixed point out there; his eyes flit helplessly across the empty sea but are constantly drawn back to what is closest, however much he tries to prevent them. He has another try and this time he manages to get a firmer grip on his words: “Oh fuck, Erkki … what do you think we should do?”

St Erik doesn’t answer. He supports himself with his hands on the rail and stares at the body down in the shallows. The body is resting face down, legs slightly apart. It seems to be a man or a boy, dressed in a white T-shirt and blue jeans, but his feet are bare.

“What if it’s someone from here?” St Olof rasps in his sandpaper voice.

St Erik still doesn’t answer. He is breathing deeply.

“Shall we turn him over … see if he’s got a wallet on him?”

St Erik shakes his head. Still says nothing. The hull of the boat thumps against a rock again. The powerful outboard motor, still in neutral, makes a dull throb. The circling gulls scream, their shadows gliding across the surface of the water.

“Bloody cool jeans, he’s got,” St Erik mutters to himself without taking his eyes off the blue jeans.

Kangarn’s boys took him to Fagerö. He arrived in Tunnhamn wrapped in an old tarpaulin they happened to have lying in the boat and he was welcomed there by common gulls, those shrill white mourners of the rocky shore. Ever since the old days Tunnhamn has had a special place for such cold and silent guests from the sea. It was a small windowless shed, grey, leaky and crooked, which stood a little to one side among nettles and hogweed and cow parsley. It was surrounded by dead boats and rusting engine blocks and the skeletons of worn-out fish traps, and old floats and split oars and broken cans and oil drums and all the rest of the rubbish that had accumulated there over the years.

That’s where Kangarn’s boys took him and they swore the whole way because he was much heavier than seemed reasonable, as though some unseen power was trying to pull him down into the ground. They laid him on the floor of the shed and threw the tarpaulin over him – it landed squint so that his bare legs stuck out from under it. In the half-darkness of the shed they were as white as candle wax.

Then Kangarn’s boys suddenly realised how overcrowded the shed had become now that the body was lying there and they hurried out into the fresh air. But once they were outside they just stood there, their strong arms hanging loose like the fenders on the side of a boat. They didn’t know what to do with themselves. Properly speaking they should have reported their find to the police immediately, but neither of them was very keen on that idea. St Erik and St Olof wanted as little to do with the authorities as possible. Perhaps they thought they had already done enough by bringing the body to Fagerö – after all, they could easily have left him in the sea. That, in fact, had been their first thought – just leave him and push off.

Something had changed their minds, however, though it wasn’t easy to say what.

At last St Erik – he was used to taking command since he was precisely twenty-three minutes older than St Olof – began walking towards the harbour with his brother in tow. It was a relief to get away from that shed. Down at the harbour each of them lit a cigarette and both remained silent for a long while. A light breeze ruffled the surface of the water in the harbour basin into little waves that resembled fish scales and slapped constantly against the underside of the landing stages. The air carried the sweet smell of tarred timber warmed by the sun, of seawater salt and the sharp iodine of rotting bladderwrack washed ashore. Swallows were flying in and out of the open doorway of Backas Isaksson’s boathouse, their twittering echoing between the walls. A wagtail on the ferry mooring flipped its long tail feathers, gulls shrieked and farther inland a willow warbler played his little flute while a flycatcher chirped his simple stanza. The sun coated the sea with a glimmering sheen so bright you had to screw up your eyes to look into it.

When you squint into the sun’s reflection on the sea and hear the sounds of the waves and the calls of the birds you can feel the tight iron band of fear around your chest easing – for a moment anyway. Because you are afraid, aren’t you, but you can’t admit it either to yourself or to your brother. You can’t admit it even to him, even though you are twins. It is no ordinary fear that tightens the ir

on band around your chest, not the corrosive childhood fear of the dark and of sea trolls and of Kangarn’s hard fists. Nor is it the sharp stab of panic that pierces your ribcage when the foaming white breakers on the Estrevlarna rocks rear up without warning in front of the boat; nor is it any other kind of ordinary fear. This is true primal terror, a terror that penetrates to a man’s bowels, that kicks his feet from under him and makes it impossible to flee. For it comes from within.

Primal terror – the realisation that you are doomed to extinction. The world holds no greater terror.

And you stand there squinting into the sun shining on the sea as the iron band tightens round your chest once more. Pictures are constantly flashing through your head: at one moment they are images of a stiff wet face, at the next of two white legs. You have no words to clothe your fear, but you must say something, anything at all. If you don’t you will be crushed as if you were a gull’s egg trampled by a boot – the shell splits and the yellow and the white run out. With difficulty you inhale, drag in air. And you say the first words that come to mind:

“Fuck, Erkii. Who do you think it was?”

You say that, or something like that. It’s not important. Words are just condensed air. The important thing is to hear your own voice.

St Erik didn’t bother to answer. He was squatting on his heels, forearms resting on his knees, which is how he often sat when he was thinking hard about something. He spat and carefully studied the gob of saliva as it slid viscously along the smooth surface of a black pebble. But St Olof can still hear his own voice. His mouth said:

“Do you think he was from the mainland? Or from the south? That seems likely given where we found him …”

A Happy Little Island

A Happy Little Island