A Happy Little Island Read online

Page 2

“Shut your gob, for fuck’s sake!” St Erik shouted, harsh and shrill. St Olof jumped back as if he had been splashed with hot engine oil.

“What the hell! I just thought …”

“You think too fucking much!”

Welcome and Unwelcome

Kangarn’s boys must have told someone about the guest they had placed in that slightly out-of-the-way shed. An anonymous telephone call was made to the emergency services, which then contacted the Storby police station. The rumours – big, black and white, and noisy as oystercatchers – flew out to all thirty-two points of the compass. The birds of rumour winged their way over the whole of Fagerö and flew on over the other inhabited islands in the Gunnarsholmar archipelago – Lemlot, Busö, Nagelskär and Aspskär. And from there to Hemsö, Stormskär, Klemetsö, Båklandet, Kökar and other islands familiar to us from books. The red-beaked birds were in a hurry. We are not talking about hours here: within little more than half an hour the whole archipelago knew that Kangarn’s boys had found a body out on Skogsskär.

A visitor from the open sea.

It was a long time since the last one.

Travellers to Fagerö and the rest of the Gunnarsholmar islands usually arrive from Örsund on the ferry Arkipelag or by Eli’s taxi boat or sometimes in their own boats. The passengers who come ashore in Tunnhamn from the Arkipelag tend to be familiar faces: Abrahamsson, who lives on Busö, on his way home from a business trip to the capital; K-D Mattsson returning from a meeting of the Archipelago Delegation; Olar’s Mikaela who has been to the dentist in Örsund with her daughter. Algot Skogster – the fellow who drives the milk lorry to the Örsund dairy twice a week – carefully eases his heavy truck down the ramp from the ferry to the quay. Then there’s Axmar, a bit unsteady on his feet, the muffled clink from his old green army rucksack hinting at what took him over to the mainland.

The Arkipelag brings in homecomers making nostalgic visits. And seamen who work week on, week off, on the car-ferry runs to overseas ports. And school pupils forced to go to the mainland if they want to progress to the upper secondary school or vocational college. And conscripts coming home on leave. And many other Fagerö people who need to cross the waters of Norrfjärden for whatever reason. Tunnhamn becomes crowded when the ferry comes in.

There are also summer tourists and sailing visitors from the north. They arrive after midsummer and disappear again at the end of July. The tourists are expected and are welcome. Their arrival provides the economy of the archipelago with a necessary life-giving injection. Pettersson at Östergrannas, who in addition to his farm runs Storby Camping and Cabins, will testify to that, as will Birger at the Fagerö General Store and Verna and Ing-Britt at the Eider Café, and other local business people.

Few visitors approach the Gunnarsholmar islands from the south, however. That’s where you encounter the open sea. The waters of the Kvigharufjärden and the Kallskärsfjärden are notoriously difficult to navigate and they are avoided by commercial shipping and yachtsmen alike; only sailors with expert local knowledge are to be found there. Many of the travellers from the south have come a long distance and few of them came voluntarily. They are often in a very poor condition when they arrive. The only decent thing to do when you come across travellers of that kind is to contact the police so that they can come and deal with the poor creatures.

Fortunately, such visitors from the south are rare nowadays. It must be ten years since the last ones came. That was an autumn of bad storms when the cargo ship Park Victory ran on to the rocks at Estrevlarna and sank. Many things floated ashore on the Gunnarsholmar islands when that happened.

If Antonio Vivaldi had served as a precentor in our part of the archipelago instead of teaching the violin in the Venice conservatory, it’s more than likely he would have called his best-known composition The Seven Seasons. Because out here in the outer archipelago we have three seasons in addition to the usual four. The late autumn freeze when the sea ice will neither bear nor break is a season all of its own, as is the spring thaw for the same reason. And as well as those two, Vivaldi would have needed to create a third extra movement in order to make an archipelago version of The Seasons, for there is a week or so around the time May is turning into June when the outer archipelago is subject to peculiar climatological conditions that can neither be called late spring nor early summer. It’s as if nature decides to take a short break after all the forceful budding and sprouting of spring, to give itself a pause to draw breath and gather strength before bursting forth in luxuriant green. The birch trees stand there with shaggy tufts of moss on their branches, the buds on the bird cherry are ready to open, the eider are relaxing in their down-lined nests after the effort of laying and are happy just to be keeping their eggs warm, and the flies, biding their time in the good heat of the dunghill, are in no hurry to fly out and plague both man and beast. Existence is hard and the archipelago allows little respite, which is why a seventh season is needed to give nature time to fill its lungs for the work of the growing season.

The people, too, seize this opportunity to recuperate after the long winter and the urgency of spring. In the old days it was good to live through this bright and airy season of the year. The spring fishery for large herring was for the most part over by this point, as was the wildfowling, though that was more for pleasure than practical purposes. Potatoes had been planted and the sheep taken out to the island grazings where they would live half-wild until well into autumn. The school children were set free from their winter-long incarceration behind desks and were allowed to run as free as the sheep.

It was a time when only the most essential jobs were done and everything else was put off until the morrow. People sat out on benches placed against the south wall of their boathouses, stretched out their legs and took deep gulps of fresh air to inflate their chests like bellows. And they smoked and contemplated life and made sure there was time to drink coffee. Women hung away winter clothes, aired the bedding, took out the inner windows, put up summer curtains, scrubbed floors, did the laundry, washed the mats, repotted plants and dealt with all the things necessary to set up the household for summer. They rushed back and forth like tree sparrows with newly hatched chicks in the nest, but they too took the time to stop and draw breath now and again. And, for all their haste, they might even be caught humming a tune.

Oh yes, it was good to be alive at that season, so bright, so airy, so filled with hope. And there was always someone who remembered to quote the words spoken by an old man long ago as he sat sunning himself by the boathouse wall one day in May: “What a stroke of bloody luck that I didn’t go and shoot myself last winter.”

Even though many things have changed now compared with the old days – and most of the people of Fagerö would agree with you on that – those weeks when May meets June are still a time when the people here on Fagerö slow down a little and put off until tomorrow whatever doesn’t actually have to be done today. They change their body clocks to summer time. They seize the chance to put the troubles of winter and stresses of spring behind them.

But then the black and white birds of rumour came flapping along, uttering their shrill cries.

They blocked out the sun. Their shadows moved over the shoreline of Fagerö, over the fields and over the houses, over the upturned faces of the people – faces that suddenly went pale. The birds called and their voices were shrill.

And the islanders felt a sudden strange chill in the air.

The Queen of Aspskär

A couple of hundred metres before the bend where the road curves down to Tunnhamn, a car of Japanese make had come to a halt behind a blue Volvo tractor with enormous double rear wheels, a shovel on the front and a trailer in tow. The tractor’s diesel engine was idling, grunting like the huge wild boar in some horrible fairy tale. The driver’s door was open. A middle-aged woman with dyed blond hair wearing green overalls, black wellington boots and a peaked cap with the words SAMPO ROSENLEW printed on the side had one elbow resting on

the roof of the car as she bent down to the open side window to converse with the driver of the car. The driver was also a woman of about fifty. She had a narrow face that was made even narrower by the large pair of spectacles with green plastic frames she was wearing. There was a third woman listening to the conversation between the other two. She was considerably younger, with solid thighs, a big backside and a round, open face with the beginnings of a double chin. Her hair was tied back in a ponytail and she was pushing a pushchair in which a child was sleeping. It was impossible to see whether it was a girl or a boy.

It was the early afternoon of a day at the end of May and the three women were standing on the road leading down to Tunnhamn. The weather was sunny and the wind speed was barely two metres a second. The midday temperature had reached 14 degrees Celsius.

There were birch trees growing at the roadside: white trunks, light airy green, and somewhere in among them a willow warbler was singing.

An oystercatcher had just flown over, calling loudly: kleep! kleep! kleep!

A hundred metres farther on, immediately before the bend down to Tunnhamn, another car was parked among the alder and sallow bushes that lined a gravel road. A Saab, painted blue and white. The Saab had searchlights mounted on a rack on the roof and a radio aerial on the rear window.

Come, let’s move in a little and find out what the women are talking about!

They are clearly talking about matters of some importance since they’ve taken the time to stop on the Tunnhamn road on an ordinary working day in the middle of the week.

“… and the inspector and Ludi have been there at least half an hour. The police car passed me when I was on my way down to Mörö Bay. They were in a great hurry. Must be some kind of investigation, mustn’t it?” the woman in the green overalls can be heard to say through the side window. She speaks in a quick breathless voice.

The driver of the Toyota tut-tuts.

“Kangarn’s boys are the ones who found him apparently,” the woman in the overalls continues. Then she falls silent and waits to see what effect her words have.

“Really? Is that right? Kangarn’s boys, was it?” the younger woman, the one with the pushchair, exclaims.

“Can you believe it? But …” the woman in the car says. And then she too falls silent as if she had been intending to ask a question but thinks better of it.

So now we know what they’re on about we can stop listening. It seems unlikely that the three women are in any position to add anything to the story at this stage.

All of a sudden the women stop talking.

No, it’s not the cuckoo which has started calling to the south that causes them to go quiet – after all, they aren’t ornithologists or twitchers. The woman in the overalls looks along the road. The rattle and clatter of a two-stroke engine can be heard from the direction of Storby. The sound swells as it approaches.

It was Judit.

She had been shopping in Storby and was riding her utility moped, an old Tunturi that she kept in Gottfrid’s shed in Tunnhamn and used for transport when she came over to Fagerö to work or do some shopping. She had five plastic bags bulging with groceries and household items piled up on the load platform. When Judit went shopping, she really did shop. She was wearing old-fashioned sea boots – the kind with the tops turned down – washed-out jeans and a windcheater on top of a Helly Hansen fleece. Around her head she had tied a blue-striped cotton kerchief, on one side of which a tuft of black hair was sticking out just where her jaw met her neck. A puukko knife with a curly grained birch handle was hanging in a worn leather sheath at her hip.

It was Judit.

That was what she was called, that and nothing else. No one used her family name, no one even called her Judit Aspskär, a naming habit which was the norm when it came to referring to people living on the smallest islands.

Judit braked to a halt. She turned the engine off, climbed off the moped and said hello. This was more noteworthy than it sounds. By stopping and greeting them, Judit was showing her respect for the two older women in particular – they were, after all, among the leading women on Fagerö. Her good manners would certainly not go unremarked.

And we should be polite, too, and briefly introduce the three women we have already described. From right to left they are Olar’s Mikaela and her youngest daughter Jenni, Elna and Mrs Councillor. Three fair daughters of Fagerö. Well, Mikaela wasn’t born on Fagerö, she comes from the mainland where Stig met her when he was attending agricultural college. Elna is married to Backas Isaaksson, and that says a great deal to anyone at all familiar with life on Fagerö. And the woman in overalls driving the tractor, the one who has just told Elna and Mikaela about the police being called to Tunnhamn, is Mrs Councillor, wife of K-D Mattsson, Fagerö’s strong man and chairman of the district council.

It might at first seem a little strange for the wife of a leading local politician to be dressed like a farmhand and driving a tractor and trailer, but there is a very simple and natural explanation. They have a farm over at Lassfols, but they have started salmon farming, a business that has gradually taken off in the archipelago now that traditional fishing is in decline. Mrs Councillor has just driven a load of pelleted feed down to the bay at Möröviken, which is where their salmon farm is. Much of the daily running of this new business rests on her shoulders since K-D Mattsson’s interminable political duties keep him busy. And say what you like about Mrs Councillor in other respects, she isn’t afraid of getting stuck in and dirtying her hands.

Her nickname itself is worthy of some explanation. It’s no great secret that K-D Mattsson had long been hankering after some sort of title as an acknowledgement of his many years of social and political involvement. Mrs Mattsson, good and loving wife that she was, was well aware of her husband’s hunger for a title and wanted to do her bit to satisfy it. She saw her opportunity a few years ago when K-D was coming up to fifty. Allowing herself plenty of time, she initiated a lively campaign of lobbying in an effort to prevail upon Fagerö District Council to propose to the government that the title and distinction of Councillor in perpetuam should be conferred upon K-D Mattsson on his fiftieth birthday. Mrs Mattsson believed she was doing her lobbying with the utmost discretion, but it soon became public knowledge. What’s more, there was an occasion when she let slip that she herself would actually have nothing against being addressed as Mrs Councillor Mattsson, an unfortunate remark that was very quickly turned against her.

Her efforts might just possibly have been crowned with success had it not been for the fact that the President of the Republic – unfortunately – does not dole out honours gratis, however well-merited the recipient may be. The payment of a rather large sum in stamp duty was demanded before K-D could expect the conferment of a title. In other words, honouring K-D in this way was not going to come cheap.

The leading members of Fagerö council – with the natural exception of K-D himself, who pretended he knew nothing – discussed the issue at a hastily convened meeting held behind closed doors at the Eider Café. It was a short meeting. On 12 May Fagerö District Council celebrated K-D Mattsson’s fiftieth birthday with the gift of a glass vase signed by the artist Tapio Wirkkala and a bunch of tulips. The people of Fagerö simultaneously awarded Mrs Saga Mattsson the title of Mrs District Councillor which, for convenience, was soon shortened to Mrs Councillor. And she didn’t even have to pay stamp duty on it.

While she was in the Fagerö General Store, Judit had heard the news of a body being washed ashore. An unspoken question had been hanging in the air in the store and she could read the same worry and disquiet in the faces of the three women here.

Judit stood with her hands on her hips, looking in the direction of the parked police car. A mosquito had sunk its proboscis into her forehead immediately above the bridge of her nose and its body was already beginning to glisten red with her blood. Judit didn’t seem to notice. She wasn’t much of a one for tiptoeing around with suggestions and half-voiced hints; that was not Ju

dit’s style.

“Has anyone been and seen him?” she wondered.

“Well, we haven’t anyway,” Mrs Councillor answered.

“That’s what I thought,” Judit said.

Judit pushed her moped to one side and walked down the road with long strides. She passed the police car and disappeared behind the curtain of alder that grew there concealing the shed.

The women’s gaze followed Judit. Their eyes narrowed. There was something more than a little pointed in their looks.

That’s Judit!

Janne the Post and other reliable spokesmen the scribe interviewed are all agreed that Judit is worth looking at. When Our Lord’s heavenly lathe was turning Judit, we might suspect that He smiled as He worked. He gave her liberal dimensions and used tough and durable timber. Judit was designed for life in rugged conditions, you might say.

She was born on Aspskär, the youngest of a family of seven. Aspskär is one of the outermost and harshest of the inhabited islands in the Gunnarsholmar archipelago. Its arable land is just about sufficient for a potato patch and, that excepted, the people have to rely on whatever harvest they can glean from Neptune’s acres. Judit wasn’t even six months old when an autumn storm took her father: he and a companion had been out drift net fishing for salmon when an unexpected storm blew up. The coastguards found the shattered wreckage of their boat over by Svenskgrundet, but there was no trace of its crew. One by one the siblings flew the nest, dispersing like a brood of young swallows. In the end only Judit was left alone with her mother and now her mother has gone too. Judit is no longer alone on Aspskär, however. For the last couple of years she’s had a girl living with her.

The girl Judit has with her out on the island is still a teenager and is generally considered to be a bit simple. Apart from that not much is known about her.

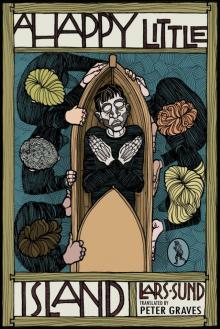

A Happy Little Island

A Happy Little Island