A Happy Little Island Read online

Page 3

Most of Judit’s income comes from fishing, along with hourly paid temp work as a care assistant or looking after cattle on Fagerö. She manages pretty well everything herself: handles the boat and the fishing, repairs the water pump when it goes wrong, fixes the boards on the boathouse, re-felts the roof of the outhouse, puts up guttering, putties the glass in the windows. When ice wrecked the Aspskär landing stage last winter it was Judit who built a new one. She hunts seals and shoots seabirds. Any grey seals that move into Aspskär waters are living dangerously since in Judit’s eyes they are pests which do serious damage and deserve to be persecuted mercilessly, preferably wiped out. She’s as good as any man when it comes to wildfowling and she makes sure her freezer is full of long-tailed duck, eider and scoter. Her seafowl soup, made with thick cream and a dash of cognac, is a culinary joy.

That’s Judit!

Our Lord certainly gave her the gift of ageing well. She’s middle-aged and a bit more, but she is still a fine woman, amazingly little worn and scarred by her work with fish traps and nets and all the other trials that existence in the most distant skerries brings. Most of the people who try to guess her age invariably make her ten years younger than she is. You wouldn’t exactly call her beautiful as she is quite weather-beaten and the skin around her eyes and mouth is a network of fine wrinkles. But her high cheekbones and strong body never fail to attract attention, and she is not quickly forgotten. Most extraordinary of all, however, are her eyes. They have borrowed the colour of the sea on a bright early morning at the beginning of July when there is a light breeze rippling the surface. It is easy to drown in eyes as blue as that.

Judit has had many suitors. All of them have been rejected.

The Queen of Aspskär – it was Axmar who christened her that one night when he was drunk in the American Bar – seems to manage perfectly well without men.

The inspector emerged from the hidden shed and the midday sun hit him straight in the face, its light dazzlingly strong and hot for eyes that had grown accustomed to the gloom inside. Instinctively he shut his eyes and screwed up his face like a small child. The corners of his mouth turned up in an empty grin, baring several front teeth, even and white. Half-blinded he dug in the breast pocket of his uniform to find a pair of sunglasses – aviator style – then fumbled with the arms since he only had one hand free. In the other hand he was carrying a briefcase with an aluminium casing. It looked to be quite heavy.

Ludi – Senior Constable Kaj Ludvig Skogster as the police register listed him, but known on Fagerö simply as Ludi – followed the inspector out of the shed. Ludi spat, took a handkerchief from his trouser pocket and wiped his mouth. There was already a smell in the shed.

Judit studied the inspector.

His name was Riggert von Haartman. Inspector Fucking Haaaartman, as the Fagerö people called him scornfully. The inspector wasn’t popular, was reckoned to be stuck-up and a troublemaker. He came from the mainland. The inspector was in uniform and his shoes were gleaming, which Judit found quite unnecessary. It was impossible to read his eyes through his sunglasses and she didn’t like that either. Judit was the sort of person who wanted to look her fellows in the eye – that was Judit for you. Inspector von Haartman still hadn’t noticed her. He turned to Ludi:

“Skogster, make sure the shed is cordoned off and put a guard on it! Then find the one or ones who found the body and brought it here. They’ve got a lot of explaining to do: this is not the way things should be done. Moving a body from where it’s found is against police regulations. I’ll see to it that they face prosecution!”

The inspector spoke in a sharp voice, cutting off each statement abruptly. You could virtually hear the exclamation marks. Ludi pursed his lips and scratched the back of his neck.

“How am I supposed to guard the shed while I’m looking for the blokes who found the body?” Ludi wondered aloud.

Judit saw the inspector’s jaw muscles tense. He opened his mouth but changed his mind and swallowed the words he had on the tip of his tongue.

“I’ll send Juslin and Danielsson over as quickly as I can once I get back to the station. I’m going there now. I’ll make a preliminary report and arrange for the body to be taken for a post-mortem as soon as possible. And he’ll have to be identified. We’ll do a computer search to see if his description matches anyone listed as missing.”

“Right, OK,” Ludi said.

That’s when Judit stepped forward: “Perhaps I can help?”

The inspector turned round, annoyed.

“What did you say? What do you want? Excuse me but …”

“Ah, it’s you is it, Judit?” Ludi exclaimed.

“It was Kangarn’s boys who found the body,” Judit said.

“What did you say?”

“Kangarn’s boys found the body and put it in the shed,” Judit repeated.

“Right, right! That’s so, is it? And how do you know about it? Skogster, we’d better see to it that this is taken down!”

Instead of answering him Judit nodded in the direction of the shed: “I thought I’d take a look at the poor devil in there.”

“Are you listening? I asked you a question!” von Haartman said sharply.

“I’m just going to take a quick look,” Judit explained.

And without bothering about the inspector she went to the shed, giving Ludi a friendly nod on the way, took a deep breath, opened the door and stepped inside.

Inspector von Haartman stood rooted to the spot, astonished and perplexed.

Ludi, too stunned to bring himself to intervene, looked helplessly at his superior.

“For God’s sake, Skogster!” von Haartman exploded when he eventually regained the power of speech. “Get her away from there! The shed is in a police cordon! I’ll throw the fucking book at her for this!”

“But that’s Judit, that’s what she’s like,” Skogster sighed, as if that could account for and explain what had happened.

The women at the roadside saw Judit emerging from the alders that screened the shed from the road. She walked round the parked police car, walking strangely slowly, or so it seemed anyway to Mrs Councillor, Elna and Olar’s Mikaela as they stood watching her approach. She was walking with slow heavy steps, head bowed, eyes fixed to the ground.

The women waited in silence.

At last Judit walked up to them. She raised her head.

Her expression was matter-of-fact. But something hard and defiant glinted in her strange, light-filled sea-eyes. The women waited for the answer to the question they didn’t dare ask, the question that was burning on their lips.

Judit shook her head.

“He’s not from here,” she said. “He’s a stranger.”

K-D Mattsson Makes a Speech

K-D Mattsson is about to make a speech.

K-D is the political leader and indisputable chief of this small community in the archipelago – or, at least, he does his best to present himself as its chief. He has been chairman of the district council for many years and thereby occupies the most important and prestigious post in the political life of Fagerö. In addition to the council he has a seat on the planning authority, the social services committee, the archipelago delegation, the district health board and the school board. He is also chairman of the local Fagerö-Lemlot branch of the People’s Party and a member of the board of the newly formed South-West Archipelago Association of Fish Farmers.

In other words, K-D’s functions and duties are as numerous as King Solomon’s wives and concubines.

Politically speaking, K-D regards himself as on the Christian democratic wing of his party. He thinks of himself as a man of the people, a keen proponent of increased support for the economic and commercial activities of the archipelago, of social equity – along with thrift, of course – in the disbursement of public funds. Depending on the particular circumstances, he has swung between supporting the liberals and the conservatives, for he has long been of the opinion that politics is the art of the possi

ble and that consensus leads to results. His ultimate aim, when the time is ripe, is to take a seat in parliament.

K-D is convinced that there is no one better suited than him to be the voice of the south-west archipelago among the nation’s lawmakers. Unfortunately, however, the electorate of the south-west archipelago does not share this view, as they have demonstrated all too clearly at a number of elections. So for the moment K-D’s hopes of a seat in parliament are about as realistic as his dream of a title.

“Do I have to wait all day for a turn to speak?” K-D Mattsson brusquely interrupts our narrative.

Certainly not. The floor is all yours!

K-D really ought to have been provided with a lectern decorated with fresh birch foliage and lilies of the valley. That would have been only right and proper given the time of year and the fact that virtually the whole population of Fagerö is present to listen to him. But he has to be satisfied with plain grey rock, which is all that’s available up at Tjörkbrant’n, as the open area around the church and graveyard is known on Fagerö.

Anyway, this podium can serve as a reminder of K-D Mattsson’s humble beginnings. Even as a little lad he had been fond of going down to the shore and, like the young Demosthenes, training his voice by outdoing the sea, the wind and the herring gulls – the scornful laughter of the latter doing nothing to dampen his oratorical enthusiasm, merely spurring him to raise his voice even more. This, of course, was all long before K-D became a pillar of society and the political leader on Fagerö. In those days he was still just Österkli Kalle from Flakaby on Lemlot, a callow effort at a human being, skinny as a rake, all bare mosquito-bitten legs and dirty feet, but with a powerful drive to make something of himself already throbbing in his breast.

“Right! Right!” K-D snorts, becoming more and more irritated.

And he steps up on to the rock, buttons up his jacket with one hand, fills both lungs with air, thrusts out his jaw and speaks:

“People of Fagerö! Dear friends!

“A few days ago a dreadful discovery was made on Skogsskär. A refugeee, brought in by the sea, was found there. That discovery has given rise to a great deal of curiosity and discussion. We are gathered here today to accompany our unknown friend on the last stretch of his journey. I want to take this opportunity to voice some of the thoughts and feelings which I believe we all share at this moment in time.

“The fate suffered by this young man was a harsh and cruel one. All the signs are that he had travelled far before arriving here, washed up on a foreign shore like a piece of flotsam. May his fate be a reminder to us all of the fact that, in the last resort, man is but a small and frail creature. May it lead us all to contemplate the transience of human life.”

Inspector Riggert von Haartman was listening without hearing. K-D’s words undoubtedly entered both of his ears, worked their way through the auditory canals and caused the usual vibrations of the tympanic membranes, but they went no farther than that. They fell into a gap behind each ear, where they remained like dead flies between inner and outer windowpanes.

Inspector von Haartman did not want to be here. He did not want to stand and pretend to listen to K-D Mattsson’s speech.

The silver lions that decorated the epaulettes of his official uniform glinted in the sunlight. Under his outer uniform von Haartman wore a second uniform, an invisible uniform that was just as carefully buttoned, its belt just as tightly buckled, its shoulder belt just as taut across his chest. It couldn’t be any other way. A mere police uniform – the visible one – was quite insufficient to hold Riggert von Haartman together, for he thought of himself as a man with loose seams, badly stitched, split from the start. Unless he started the day by buttoning up his invisible jacket of will and pulling his belt of duty as tight as it would go around his waist, he would, in no time at all, fall apart like the rotting corpse of a seal. Then everything inside him would run out, black, putrid and stinking.

Riggert von Haartman was indeed badly put together and rotting inside.

That is what he had been taught at a very early age. It had been knocked into him brutally.

K-D Mattsson continued.

“I referred a moment ago to a foreign shore. But for us, of course, that shore is anything but foreign, it lies in our home, in the archipelago we love and call our own. Ever since the first seal hunters found their way out here during the Bronze Age, these Gunnarsholmar islands of ours have been inhabited. Our forefathers drew their livelihood from the sea and bit by bit cultivated the land, laying the foundations of our present society. Even today there can be no doubt that the famous words of the poet Runeberg are an apt description of our Fagerö: ‘Our land is poor and will remain so/for those who lust for gold …’ Outsiders perceive our circumstances as small and narrow. We may well lack some things the city can offer and cannot claim to have the same high standard of living as city people have. There are many ways in which we have to manage for ourselves and rely on our own resources. The depopulation of the archipelago is one of our great concerns – our young people leave in search of education and a livelihood, and our demographic structure becomes ever more disadvantageous.

“In spite of all this I would claim that we are rich! Our wealth may not perhaps be visible in our tax returns, but we are rich – richer than most people! We all have food, we all have clothes, we all have shelter. There is no real unemployment in the Fagerö district and the social welfare of all our people is well taken care of. We have our school and our social security. We are bound together by our language and by the culture we have inherited from our forefathers. We have built our society on the core values of Nordic democracy. We are not prey to unnecessary pressure and stress. We live in harmony with nature and make the time to help and support one another whenever necessary. Out here in the archipelago we are healthier and we live an average of five years longer than the general population.

“Is all this not worthy of being called wealth, dear people of Fagerö? Do you realise that you have won first prize in the lottery? Being born on Fagerö – that, my friends, that is the greatest prize.”

Pleased with his analogy K-D made a short rhetorical pause to give the people of Fagerö time to contemplate their good fortune. There was a sudden island of silence in the flow of words and Inspector Riggert von Haartman woke up.

For a short moment he had no idea where he was.

Then he remembered. The churchyard. Tjörkbrant’n.

And it was full of people.

They had walked in procession from Tunnhamn up to the church. The procession had been led by Janne the Post, Fagerö’s official standard-bearer, with the flag of the republic at half mast. Behind him walked the two fiddlers Axmar and Fride, sawing away at Mendelssohn’s March op. 108 at such an improbably slow tempo that it was unrecognisable, but on the other hand it did last all the way up to the churchyard with no more than a couple of repeats. Then came Assistant Pastor Lökström dressed in an alb and red stole, and carrying the prayer book in his folded hands. After him came his wife, Deaconess Hildegaard Lökström, followed by Lindman the organist, K-D Mattsson, Backas Isaksson, Abrahamsson from Busö, Berg – the chief executive of the local government – and their respective wives. They were followed by the rest of the population – all in all, a lengthy cortège.

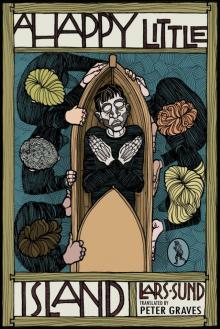

The cause of the procession came next in line behind the flag. He was carried on a handcart borrowed from the Fagerö General Store and drawn by four strong men under the command of Senior Constable Skogster. The coffin looked a little strange, a result of the social welfare committee having decided to have it made locally rather than send for a factory-made coffin from the mainland. It hasn’t been possible to discover the thinking behind their decision, but we must assume it was taken for reasons of economy as well as social policy.

These days the inhabitants of the archipelago usually turn to funeral directors on the mainland when the need arises. The art of building coffins died out long ago out here, along with a great many other traditional

craft skills – Sylvius on Domaskär is reckoned to have been the last Fagerö local to have been buried in a coffin he built himself and that was more than thirty years ago. So it had been a matter of calling on what skill was available locally, which meant that the order had gone to Karl-Gunnar Blomster in Söder Karleby, Fagerö’s only surviving boatbuilder. He was actually retired these days and spent most of his time carving models.

It was all a bit of a rush. Even after investigating the case for a week the police had been unable to establish the identity of the drowned man, and for obvious reasons the authorities felt forced to give permission for him to be buried.

Out of long-standing habit Karl-Gunnar modelled the coffin on a clinker-built rowing boat, making it a little smaller and, of course, fitting it with a lid. In his haste he didn’t think it through and consequently fitted a small keel to the coffin, just as he had done with his boats. The keel, as might be expected, was a less than successful touch since it caused the coffin to cant to one side whenever it was set down. There was, however, no time for modifications and they had to make do with propping up the coffin with planks, as with a boat when pulled ashore. Apart from that, Karl-Gunnar’s coffin was considered to be a sound piece of work, if somewhat heavy. And it was certainly a vessel capable of carrying an unknown man on his last journey.

The funeral service took place in the open air, that still being the custom on Fagerö. The churchyard was crowded and there were far more people standing on two legs above ground than the few who were resting on their backs beneath the earth. The service was soon over and done with: Assistant Pastor Lökström had said a few words, prayed a short prayer and blessed and committed the body to the peace of the grave. Led by the precentor the people sang Hymn 522, “Be with me, for eventide has come”. And then it was K-D Mattsson’s turn.

A Happy Little Island

A Happy Little Island